.

Ecstatic.

Wrung-out.

Longing for more.

This is how you feel when you shuffle-float your way out of Blue Is the Warmest Color – suffused with a little of that warmth but a little afraid that the world outside is a little colder and a little grayer than the one you’re leaving behind.

It’s one of those rare movies that you find yourself shaking your head over for days afterwards, wondering about, wishing you could somehow get back to. Its protagonists are so well acted and so irresistible that it strikes you as one of life’s great disappointments that you’ll never meet them, never have them over for dinner, never run into them on the street and a grab a spontaneous cup of coffee.

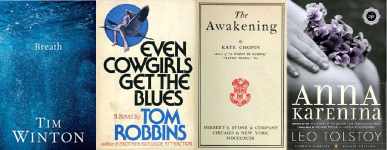

I usually only feel this way about characters in novels, and only the very best of them at that – Eva Sanderson, Sissy Hankshaw, Edna Pontellier, Anna Karenina – but Adèle is that magnetic, and Blue is that grand. Not that epic (at least as AK) but definitely that grand.

The compensation for not being able to take Adèle home with us (besides the fact that she doesn’t throw herself under a train, thank god) is that we got to see her at all. That, as A.O. Scott puts it, “For a while, her life is [ours].”

À la Tennyson, it’s better to have been with Adèle for a few hours in a movie and lost her than never to have had her at all.

Blue Is the Warmest Color might not change my life in any momentous way, but it’s certainly had an effect the last few days, and I imagine that Adèle and her relationship with Emma and with life will continue to surface from time to time, as with the best of my literary heroines, and make me grateful for the fact that despite terrorists and the Tea Party, we still live in a world where such beautiful characters are made.

Part of the reason you love Adèle so much is because you see so much of her.

I don’t mean that crassly, though there is enough skin in the movie to justify such an assumption. Yet, in addition to her emotional breadth and depth, I do intend a physical, visceral meaning of “so much of her.”

Pic: NYTimes

We see Adèle in almost every shot of the film, and even when she’s not doing anything there’s a potency to her. Whether she’s waiting on a park bench or riding the bus or watching her kindergarten students nap, she communicates a stirring vibrancy. Every one of her pauses is pregnant. The shots of her sleeping, and there are quite a few, are extreme closeups of her feet, her hips, her neck, her lips. She’s positioned athletically, as if caught mid-motion, and she’s breathing heavily, almost snoring, her mouth agape, drool all but dribbling out. Point being, Adèle doesn’t simply rest at night. Sleeping for her is an activity, evidenced in another way by her dreams – vivid as anything else in the picture, and as real to her as she is to us.

And if there’s that much vitality when’s she’s not doing anything, you can imagine how much energy she brings to what she does. She’s an unapologetic gourmand and the gusto with which she eats is often on display, especially early in the film, and leaks over into everything else. She smokes and writes and drinks and laughs and dances and reads and cries with an urgency that transcends the desperation of her teenage years and early twenties, and you find yourself wanting desperately to be a part of it, highs and lows, triumph and heartache alike.

The rough storyline: Adèle, a junior in high school when we first meet her, is trying to navigate the world of her blossoming sexuality and her deeply romantic character. She tries with boys and it doesn’t fit, so she throws her lot in with Emma, a grad student in painting at the Beaux Arts. Laughter and love and sex and soul-bearing and betrayal and tears and snot and pain ensue.

The intensity of Adèle’s engagement with life creates in the half-dozen or so years we’re with her some extraordinary moments of contentedness and connectedness and bliss. It’s also, of course, her undoing. The specifics of this I won’t get into, though by the time you’re halfway in you’re pretty sure what’s going to happen, and you immediately start praying it won’t. I will say, though, that the yes-we’re-really-done-for-good scene was the most heartbreaking I’ve ever seen.

Hell, it was more heartbreaking than all but one of my own real-life yes-we’re-really-done-for-good scenes (which, luckily, really wasn’t).

Pic: Reverse Shot

Since superlatives seem to be the rule in Blue, the scene in which Adèle’s school friends try to shame and taunt her into outing herself at a public bus stop after they witness one casual encounter between Adèle and Emma is the best approximation I’ve seen of the rage, shame, frustration and fear such a situation must entail. I’m not gay and nothing like that has ever happened to me, so maybe I’m off the mark, but it was devastating.

Which is probably the phrase I’d make the sub-subtitle of the movie, if it were up to me: Devastation guaranteed.

There are a ton of other things to talk about in the movie: the class implications, the representation of art and artists, the sexual politics (is it self-conscious or is it prurient male fantasy?), whether it can transcend its NC-17 rating (it deserves to), that bullying/outing scene, and most interestingly, original author Julie Maroh’s reaction to the whole thing.

I’m not that worked up about the sex itself – the scenes were long, they were intense, they could break through anyone’s hungover Puritan prudeness or world-weary coolness (well, anyone but NYC film critics, of course) – but it was only part of the whole emotional banquet that director Abdellatif Kechiche lays out for us. And that – the experience of being briefly but wholly integrated into a fully conceived world – was the most interesting part of the movie for me. Adèle Exarchopoulos, who played Adèle, said in an interview, “We [Léa Seydoux, who played Emma] had to show how making love to someone is visceral. We had to convey how much of yourself you give over,” and they did that, in the meta- sense of imbuing the fictional story with their own real-life courage and trust in one another, as actresses.

What’s more, whose sexual politics are pure and correct and unburdened by the myriad issues and hangups of modern society and our own irrational desires and fantasies? We don’t write off Anna Karenina, or Anna Karenina, because Anna and Tolstoy had questionable morals and worldviews. Instead, we love Anna because she dared to love and live her life in ways that most of us aren’t capable of, precisely because she didn’t care about the strictures that society and/or anyone else tried to put on her passions.

Devastation is commensurate with the bliss it succeeds.

We all know this to some degree or other, and we live our lives accordingly. The vast majority of us hedge our bets, sacrificing what we assume or suspect or even downright know will be blissful for fear of the devastation that may come of it. Anna Karenina wasn’t willing to bridle her passions or curb her excesses, which actions amount to the willingness to risk their cost ahead of time, without knowing or caring what those costs may be.

We love Adèle because she dares to do the same.

And I aspire to demonstrate half her courage.

Anyway, look at the preview, and then tell me you don’t want to see it.

If you have seen it, what’d you think?

If not, go! and then come back and tell me.