I love soccer.

I love playing it, I love watching it, I love reading about it.

(I’m horrrrrible, I rarely see games, and I do so very slowly to “practice” my equally horrible Spanish, respectively.)

So I was thrilled that Jozy Altidore came through big against Honduras Tuesday night and got us/U.S. one step closer to a World Cup berth. (Chances are bad they’ll do it in one more game, but great they’ll do it in two.)

I’m also enthralled by all things Brazilian, so this World Cup is especially exciting for me. At one point some years ago, a bunch of us were planning to roam through Brazil together, see some early round games in the smaller cities, and try to just be in Rio or Sao Paulo for the finals.

But there are some serious protests going on in cities all over Brazil, and I gotta say, I kind of see where they’re coming from. Protests started over a 20-cent bus fare increase, and then BLEW UP after rather brutal reactions by various police forces (unlike Turkey, the media’s covering the heck outta Brasil’s protests).

Most apropos to this post’s lede, the demonstrations are also fueled by general indignation over the high costs – both financial and personal – of preparing for the very 2014 World Cup that I was planning (until life happened) to attend.

A Copa do Mundo next year, and the Summer Olympic Games two years after that. According to the WaPo, stadium and public transportation construction costs are estimated at $14.6 BILLION for EACH the World Cup and the 2016 Games. True, the construction projects will employ a lot of people – 3.6 million between the two projects – but they’re only temporary jobs. And there’s not really any space for these facilities, or at least for the ones that’ll be right in town, and the people that are being moved to make room for those new facilities are, as usual, the poor and powerless. And not just asked to leave for a bit before coming back after the Games – I’m talking entire favelas being ‘dozed to make room for new facilities.

This is the case everywhere, right – whenever there’s a GIGANTOR sporting event, people get displaced. Even in Atlanta, where it seemed like there was still plenty of room, in the good ole rich-and-wealthy USA where everyone’s treated with the utmost respect and dignity, Olympic construction still wrecked major havoc on people’s lives. While not nearly as many people were displaced in Atlanta as in Seoul (725,000) or Beijing (as high as 1.5 million), those whose neighborhood was destroyed were still among the city’s poorest. Thousands and thousands of people living in public housing sandwiched between the Coca-Cola plant and Georgia Tech were packed on buses, given a one-way ticket out of town and wished the best of luck, in order to make room for the Olympic Village and the housing of 10,000 athletes. Only 7% of those people returned to their old neighborhoods and the rebuilt homes promised them by Team USA and Atlanta city planners. Basically, the Olympics gave the latter the opportunity they’d been waiting for to “wipe out blight” (read: relegate poor blacks to the sticks) and complete the gentrification of certain neighborhoods.

Even in London, where the 2012 Games were, most of the people displaced and/or affected by stadium construction and the influx of new residents and attention were from the other side of the (both proverbial and literal) tracks. Check out Zed Nelson’s great photos of London’s rough-edged Hackney to see what I mean.

But Brazilians aren’t taking this action lying down.

A 6/21 UK Guardian article goes into more detail.

Photo: Cintia Barenho from “The Displacement Decathalon” article at the Design Observer site.

If you want more info on this whole Olympic displacement stuff, Lawrence Vale & Annemarie Gray have written a thorough and detailed examination of what they’re calling “The Displacement Decathalon” over at Design Observer. (If you’re an equal housing opportunity type person, I highly recommend reading with a sturdy G&T and at least three stress balls close to hand.)

Much of this might not be news to you. What interests me is what people think of it.

This is the diving well built for the 2000 Athens Games. Nice, right?

Click for a NatGeo slideshow of others.

Economics aside, is it worth the hassle?

I know it’s ethically wrong (or at least terribly disagreeable) to displace entire communities to make way for a fancy gym that the world’s elite* will use for a few weeks. Especially when those facilities crumble into disrepair in a matter of years after the event has ended.

On the other hand,

I believe in sport and international competition.

I swam until age 22, and growing up – this was before more than one or two people could make a living swimming – the Olympic Games were THE ultimate goal for me and everyone I knew. For those I know who’ve gone to the Games, they’ve lived up to every promise, every hope, every dream. The brotherhood, the camaraderie, the very idea of the Olympics – and the World Cup, and any other international competition – are some of the most inspiring things I can think of. And let’s face it – the world likes being inspired on the scale of spectacle.

But is that inspirational spectacle ultimately idealistic, rosy-glassed and unrealistic? Are those heartwarming/-wrenching Bob Costas stories of tribulation and triumph that we all love so much really kind of just self-indulgent, if the very place where one triumph happens is also the site of another – and likely worse – tribulation? A tribulation planned for and arranged by plastic-smiling organizers pandering to TV markets and big-big wallets.

But what are the alternatives? Are there alternatives?

How much of a difference would it make if the Games were held in the same place every year?

To Olympians? To spectators?

By the time I was 13 and knew what a travel meet entailed, I didn’t care where a competition was. Fargo or Fort Lauderdale or Florianópolis, you’re really just shuttling between your room and the pool.

But if the spectacle disappears – and it’d at least diminish with a static venue – and the money disappears, would the Games and other international competitions disappear, too? That’s not a problem if you don’t think that sport does anything, but if you think like I do that sport has great potential to encourage civil rights, then the disappearance of international competitions is something to be quite concerned about indeed.

Better yet, let’s get the UAE to build some ridiculous portable underwater and/or floating facilities that could be moved every few years to just offshore of and/or into the airspace above a different country. I guarantee you, a hovering Olympic Village wouldn’t let down a single athlete. And plenty of people would tune in to see.

What do you think?

Where’s the balance between spectacle and respect?

Do you care where various Games/Cups/games are?

*Almost all of them are athletically elite, and many are also “elite” in the way Americans use that word to mean “filthy rich.”

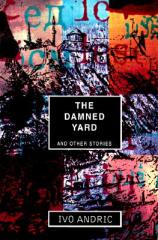

In his collection The Damned Yard and Other Stories, I hoped to get a feel for what early 20th century Bosnia must have been like. While there wasn’t that much insight into what might have compelled Princip, man, what a world Andrić paints. Myths and legends from the days of yore, rivalries and grudges centuries in the making, medieval rituals and modern thought carried out throughout the country, from tiny village to small town to big city.

In his collection The Damned Yard and Other Stories, I hoped to get a feel for what early 20th century Bosnia must have been like. While there wasn’t that much insight into what might have compelled Princip, man, what a world Andrić paints. Myths and legends from the days of yore, rivalries and grudges centuries in the making, medieval rituals and modern thought carried out throughout the country, from tiny village to small town to big city.

But the stuff about the snail isn’t (for me) the most interesting part of In Search of Memory. It was Kandel’s search for one of his own memories – his dedication to that search, and the weight that memory has – that was so compelling.

But the stuff about the snail isn’t (for me) the most interesting part of In Search of Memory. It was Kandel’s search for one of his own memories – his dedication to that search, and the weight that memory has – that was so compelling.

One thing any seven year old knows is that one thing these things are really good for is throwing into the dirt.

One thing any seven year old knows is that one thing these things are really good for is throwing into the dirt.