One of the reasons the water industry is so interesting is that it deals with fundamental questions of human nature.

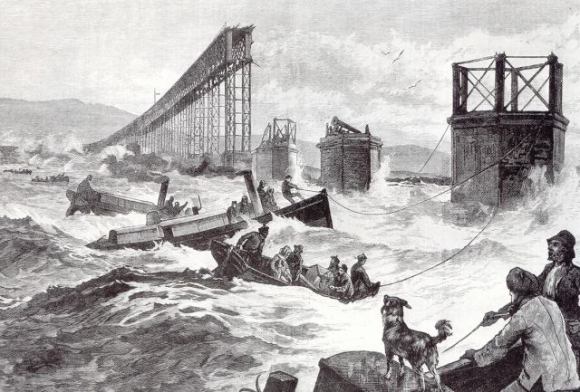

Pic from Les Catastrophe Dans Le Monde

I know, I know, that’s not Heidegger out there reading your meter or fixing the leak in your street or turning a valve or fitting a pipe. Though, if it’s an August afternoon when the sun’s so bloody hot it’s softening the asphalt, he may well be wondering just what exactly he’s doing with his life. He is, however, ensuring that at least for the time being you don’t have to worry your own pretty little head about any Sartrian questions, either. For there’s nothing else in our cushy American lives that can cause us to confront our sense of civilization more effectively, nothing that shifts from a mundane fact of life to a visceral, animal need so quickly as water.

Or, more precisely, its absence when you turn the tap on and nothing comes out.

Just how rarely that happens in the US is a testament to how well those meter-readers and leak-fixers and valve-turners and pipe-fixers do their jobs (and how well those of us inside our cubicles and offices do ours, if I may be so bold).

But ultimately, it’s mostly due to a great streak of luck.

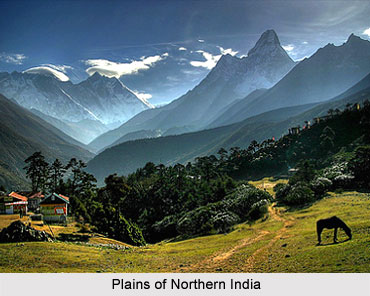

This is the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta east of San Francisco, home to California’s State Water Project, the largest publicly built water and power production/conveyance system in the States. Snow falls in the Sierra Nevada Mountains and runs off into the Delta, where, instead of flowing out to the Pacific via the San Francisco Bay, it’s diverted and pumped into the California Aqueduct, in which it flows 300-500 miles south to come out of faucets in Los Angeles, Riverside, Imperial and San Diego Counties.

This is the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta east of San Francisco, home to California’s State Water Project, the largest publicly built water and power production/conveyance system in the States. Snow falls in the Sierra Nevada Mountains and runs off into the Delta, where, instead of flowing out to the Pacific via the San Francisco Bay, it’s diverted and pumped into the California Aqueduct, in which it flows 300-500 miles south to come out of faucets in Los Angeles, Riverside, Imperial and San Diego Counties.

It’s like Londoners turning on the tap and getting water from the Pyrenees.

Which is only slightly less impressive than the Roman aqueducts of yore.

Which is only slightly less impressive than the Roman aqueducts of yore.

25 million+ people drink State Water Project – SWP – water, and god only knows how many acres of citrus, avocados, strawberries, kale, cauliflower, celery, flowers, etcetera, etcetera, etcetera are watered with it.

Ventura, where I grew up, has been around a pretty long time, at least by West Coast standards, and has always subsisted off of the local rivers and the groundwater aquifers under the coastal plains. It still does, importing zero water from the SWP. The last person to try bringing western Ventura County water from LA was William Mulholland, long before the SWP. (It didn’t work out so well.) The rest of the county east of the City of Ventura, however, does not, and would still be little more than a few small dusty stops along a much-more-often-used railroad. Construction on the SWP started in the late 1950s, got a huge chunk of money in 1960, and was completed within a decade. The cities of Thousand Oaks, Camarillo, Simi Valley and Moorpark in eastern Ventura County were incorporated 1964, ’64, ’69, and ’83, respectively. Simi had only 10,000 residents when it incorporated; today it’s home to nearly 125,000 souls (read: vacuous corporeal forms).

Imported water brought these cities into the world, and imported water would take them out.

Or the lack of it would. But before I get to any fundamental human questions about what we’re willing to do to ensure our continued existence, let me widen our spacetime lens a little more to explain why imported water would ever disappear in the first place.

The Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta is about 1,100 square miles and once had more than 500,000 acres of marshland. Since about, oh, 2300 BCE, it was home to about 15,000 people. The Spaniards and then the “Mexicans” moved in and raised those numbers a bit, but it wasn’t until the mid 19th century, when whatever failed 49ers didn’t die of malaria or dysentery realized the agricultural potential of the Delta, that the friendly neighborhood-minded white folk started streaming in and really kicked up the census numbers. Their idea, in good Anglo-Saxon fashion, was to maximize the shit outta the Delta’s potential, at whatever cost to those already there, and by whatever hook or crook they could find.

They started with by draining the Delta and building levees.

Levees, rivers, farms in the Delta.Pic: Edward Burtynsky, National Geographic

from The Boston Globe

For decades and decades the place expanded and people diverted more and more water around not only the famous paddies of California Long-Grain Rice, but also fields of corn, various grains, sugar beets, tomatoes, asparagus, etcetera – all by taking dirt, stones, wood, glass, concrete, sand, metal scrap, wagons, tractors, eventually cars, whatever, any and all agricultural, residential and industrial waste/material that was at hand and chucking it into a foundation and covering it with dirt and sometimes cementing and graveling the whole thing over. As all this crap rots and corrodes and does or does not settle, it leaves pockets in the levees, which is less than good for their structural integrity, leading many people to interpret reports by the Army Corps of Engineers to mean that portions of the Sac-SanJoaq Delta are worse off than Nawlins levees were pre-Katrina.

Which means, a little tremor here, a little tremor there, and kapow see ya later Delta system.

The fact that this hasn’t happened yet is what I meant about luck.

Because we all know The Big One’s coming, right? It’s certainly what every Californian says in response to every other act of god or nature anywhere else on the newsworthy planet.

“Man, d’you hear about Boulder?”

“The flooding? Yeah. Gnarly, right?”

“Really is. But, I mean, we’re due, man. We’re totally due.”

“For sure.”

But really, chances are pretty good that a quake is coming. So good that it’s a When formulation, not an If. The only if is whether it’s in the right place, or even the right general area, and it it’s the right strength. Because if it is, the Delta will fail, and parts of Southern California will. be. out. of. water.

And not just for, like, a couple hours till that guy with the blue collar comes and works and sweats in your street (and three of his buddies – er, “coworkers” – stand around watching) until things are fixed.

And there’s no real safeguard against that almost inevitable eventuality.

Yet. (we’re getting there)

Water wholesalers in eastern Ventura County, and most of the Greater LA Area, including parts of the OC and the Inland Empire, have decent amounts of storage, enough for about 6-9 months depending on usage and weather. But anything serious enough to take out the Delta for that long is going to take a lot longer than that to fix. Beyond that, LA and areas south and east of the city have or can get Colorado River water, meaning they’ll continue to at least be able to drink and eat and feed their pets and wash their children. Eastern Ventura County has no other source. None. There is no physical connection to the system that drains the Colorado River. The City of Ventura and Ojai aren’t going to send over any of their water – they have their own mouths and hippies and horses to keep hydrated and hygienic. And there isn’t much more than a couple months’s worth of even seriously reduced demand in our groundwater basins to support the entire area. And as of now, there aren’t any ocean desalination projects even being conceived around here (except right here, not At but inside the Wellhead, if you know what I mean). And, as an added benefit, all the farming that’s taken place over the years and all the groundwater pumping has led to such serious land subsidence that a lot of the Delta floor is 20, 25, even 30 feet below the tops of the levees, which happen to be right around sea level. Meaning if the ocean somehow backs up far enough past the Carquinez Strait and tips over into that low-lying Delta, it’ll set up a siphon like God’s own firehouse and turn those 1,100 square miles into the Great Salt Lake West.

Water wholesalers in eastern Ventura County, and most of the Greater LA Area, including parts of the OC and the Inland Empire, have decent amounts of storage, enough for about 6-9 months depending on usage and weather. But anything serious enough to take out the Delta for that long is going to take a lot longer than that to fix. Beyond that, LA and areas south and east of the city have or can get Colorado River water, meaning they’ll continue to at least be able to drink and eat and feed their pets and wash their children. Eastern Ventura County has no other source. None. There is no physical connection to the system that drains the Colorado River. The City of Ventura and Ojai aren’t going to send over any of their water – they have their own mouths and hippies and horses to keep hydrated and hygienic. And there isn’t much more than a couple months’s worth of even seriously reduced demand in our groundwater basins to support the entire area. And as of now, there aren’t any ocean desalination projects even being conceived around here (except right here, not At but inside the Wellhead, if you know what I mean). And, as an added benefit, all the farming that’s taken place over the years and all the groundwater pumping has led to such serious land subsidence that a lot of the Delta floor is 20, 25, even 30 feet below the tops of the levees, which happen to be right around sea level. Meaning if the ocean somehow backs up far enough past the Carquinez Strait and tips over into that low-lying Delta, it’ll set up a siphon like God’s own firehouse and turn those 1,100 square miles into the Great Salt Lake West.

And then sayonara basically everything. For years.

This isn’t fear-mongering or sensationalism. Ask anyone in the water industry about the Delta, and after seventeen or eighteen seconds of hemming and hawing, they’ll say, “Well, yeah, I mean, it’s basically fucked.”

Ask them what’s being done to prepare for it, and you’ll get a heavy sigh and a look that says, “Bro, we are so not on the clock right now, and I don’t want to think about work for the amount of time it’ll take to explain it to you.”

So I’m gonna save them the trouble – next week, when I get into that. I figure this is enough to digest for now, and a decent place to stop. The Fundamental Questions About Human Nature will also come next week, because they’re part of the solution. Or rather, the barrier to one being devised.

Till then, be well. And if you’re in SoCal, enjoy your shower – it may be the last one you take for a long, long time…

jk.

not really.

(Though at the same time I don’t mean to overstate how “hard” it is – even ultra-marathon-running

(Though at the same time I don’t mean to overstate how “hard” it is – even ultra-marathon-running

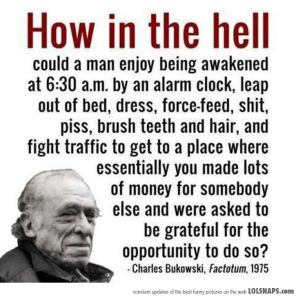

Don’t get me wrong – they’re not simpletons or noble savages. They have their shit to deal with, and their interests are wide and their understandings of the world deep and some of them are dedicated to a lot of things outside of work, but to a certain degree, they’re parking in the shade. It’s a pretty cush gig – at least, not a whole lotta what you call whip-cracking. Plenty of people would love to have this job, and most everyone here is to proud to, and most of them are grateful for it, “especially in this economy” and all that. So it seems kind of reductionist of me to say, “Meh, it’s just my day job, whatever, it’s not even a big deal.” That’s where my self-confidence and goals (daydreams) and discontent tip into arrogance. And I find myself there quite often.

Don’t get me wrong – they’re not simpletons or noble savages. They have their shit to deal with, and their interests are wide and their understandings of the world deep and some of them are dedicated to a lot of things outside of work, but to a certain degree, they’re parking in the shade. It’s a pretty cush gig – at least, not a whole lotta what you call whip-cracking. Plenty of people would love to have this job, and most everyone here is to proud to, and most of them are grateful for it, “especially in this economy” and all that. So it seems kind of reductionist of me to say, “Meh, it’s just my day job, whatever, it’s not even a big deal.” That’s where my self-confidence and goals (daydreams) and discontent tip into arrogance. And I find myself there quite often.

I have to imagine this results in part from a very American sense of entitlement. We’re taught that self-employment is the key to happiness, or at least that it’s the full embodiment of the American ideal, and that it’ll bring us riches and a sense of self-sufficiency unrivaled by the drudgery and servitude of working for someone else. One of the more nefariously defeating Myths of America is that everyone can and should make his own way to greatness in the world, when really that’s just simply not possible, for a panoply of reasons we all know by now (right? Right).

I have to imagine this results in part from a very American sense of entitlement. We’re taught that self-employment is the key to happiness, or at least that it’s the full embodiment of the American ideal, and that it’ll bring us riches and a sense of self-sufficiency unrivaled by the drudgery and servitude of working for someone else. One of the more nefariously defeating Myths of America is that everyone can and should make his own way to greatness in the world, when really that’s just simply not possible, for a panoply of reasons we all know by now (right? Right).