Go on, it’s only a thousand words, we’ll wait.

K, all caught up on just how precarious SoCal’s continued existence is?

Great, then on to solutions.

Solutions to the imminent collapse of the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta have been proposed since the State Water Project was inaugurated. The most well-known of these is the Peripheral Canal, which would divert Sacramento River water through or, as the name would suggest, around the Delta, to the tune of $3 to $17 BILLION, depending on who you’re asking. A ballot initiative to fund a peripheral canal was first proposed and defeated in 1982. A $11.14b water bond was defeated in 2010, and another is slated for the 2014 ballot, though it’ll likely be pushed to 2016. By which time it’ll hopefully be irrelevant, and Governor Jerry Brown’s Bay Delta Conservation Plan will be on its way to being a reality.

So, if it’s been an issue that people have known needs to be addressed for so long, why’s it never been solved?

Because money, of course.

On one hand, farmers and environmentalists and various other interest groups in the Delta have beaucoup bucks to throw at defeating these bills, and on the other, no one really wants to pay for it. It would certainly make water more expensive, but like car maintenance, the longer we don’t pay for it, the more expensive the project and our water will be later.

SWP water has doubled in the last ten years, and is expected to double again in the next ten, and people aren’t too excited about paying over and above what are already some of the highest water rates in the country.

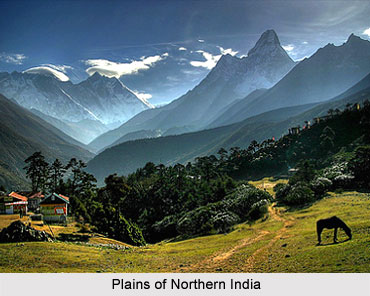

The scarcity that’s driving the cost of SWP water up is both real, and legislated/judicial. We all know about the generally shorter and warmer winters and less precipitation going on these days, and whether you believe climate change is a result of human activity or not, the fact of the matter is that there’s been less snowpack in the Sierras at the end of spring for a dozen+ years running, which means that there’s less water in the Delta. Which has led to less, warmer, more algae-filled and even sometimes saltier Delta water, to which one little linchpin in particular in the whole web of life really takes exception.

A better, more detailed description of Smeltgate than what I offer here.

Pic: NYTimes

These are Delta Smelt.

When they’re unhappy, the salmon that run in the Delta are unhappy, and as the Steelhead and Chinook are on the endangered list, Smelt have become the focal point of the ecological studies – and rage – in the Delta. In 2007, pumping allocations out of the Delta were throttled way-way back (think, half), in large part because of concern over these little buggers. A 2008 study supporting those allocation limitations stated that the Smelt, et al, were disastrously imperiled, so things were tight for a while, until Judge Oliver Wanger said in his 2011 appeal opinion that the study was carried out in “bad faith,” its findings “arbitrary, capricious, and unlawful,” the science that underpinned them “sloppy,” and the testimony of biological experts “false.” The 2007 limits were reversed, water flowed and Wagner was a hero for a day. (To some – he’s a murdering thieving bastard to fish-lovers and Delta farmers, but he’s retiring so what does he care).

Anyway, this back-and-forth is par for the SWP course, with Delta farmers demanding enough water for their crops and stoking and flaming Smelty controversy, and Central Valley Project water people saying they don’t want to pay for all the water that goes to what they think are basically water libertines in SoCal, and SoCalers saying wtf we didn’t invent this mess we just live here and we need water and btw we don’t give a rat’s ass about those little fish or about your sunken farms.

Which, no, is not helpful. Any of it.

But that’s the way the issue’s been framed after all this time: you’re either all for killing off all 57 endangered species that live in/depend on the Delta, or you’re in favor of dust-bowlizing Southern California completely out of existence. There’s no real middle ground, and there hasn’t been much in the way of an alternative. And meanwhile, prices just go up. And up. Aaaannnndddd up.

If you’re wondering, amid all this, why there were no Smelt-protections built into the SWP to begin with, you’re forgetting what the environmental regulatory environment was like in the 1950s.

There wasn’t one.

We were post-war booming then, right, flexing all those third-industrial-revolution muscles, basking in the glory of having made the world safe for democracy, believing that the world was our proverbial oyster and that we could do no wrong, including environmental harm. Not entirely their fault – there wasn’t the same awareness or even knowledge as there is now of the impacts of the human stain on the environment. I mean, we were testing the effects of nuclear fallout on human beings only what, fifteen, twenty years before?

To put things in perspective: the Environmental Protection Agency was formed in 1970. The Clean Water Act was passed in 1972. Which yes, was when Richard Nixon was President.

You know that if Tricky Dick was signing legislation for the environment, it was in prreeeetttty bad shape — and the SWP was designed fifteen years before that.

Which is why the Bay Delta Conservation Plan I mentioned earlier is such a great idea.

The BDCP is different because it addresses both water supply and environmental issues, and even goes so far as to call them “co-equal goals.”

Basically, two 25-foot-diameter tunnels would run 17 miles underneath* the Delta and all its messed up terrain and fragile levees, and connect with the existing aqueduct for the trip south. The tunnels are pared with a massive conservation plan that would, in addition to a host of other good things, restore about 145,000 acres of wetlands. (Remember, wetlands used to cover 500,000 acres, so that’s not too shabby.)

The other big problem with pre-BDCP water bonds is that as much as people say they want things to change, while they say they want secure water, they don’t want to pay for it (LATimes had a great story on this a few days ago). This hesitancy to pay an extra hundred bucks or so year is one of the ridiculous things about first-world entitlement: people will pay twice that each month for unlimited texting, or 20% faster internet, or the DirectTV sports package, or a few dozen bottles of smart water, but heaven forfend that the very thing that keeps us alive, that wars are fought over, today, still, cost you an extra few bucks a month.

Which is why Jerry Brown isn’t proposing that the BDCP go on the ballot. It’s about $24billion, $15b or so of which is construction of the tunnels, with the balance going to environmental projects. The Central Valley Project and the Metropolitian Water District of Southern California will split the cost of construction, passing it along to customers over 50 years. That comes to about $4 extra a month for the average household, and while times are tight, I know, that doesn’t seem likely to be any kind of back-breaking straw.

State and federal governments will sign on to come up with the money for the conservation side of things. Which they’ll do about half of. Maybe.

But still – that’s a lot better than what’s been done for the Delta lately. And what is likely to be done for it if the BDCP doesn’t fly.

Of course, even if ole Moonbeam gets all the required Federal permits to build in endangeredspeciesland, there’ll be Circumlocution-Office-worthy numbers of lawsuits and injunctions and every other legal instrument created by god and man brought down upon his and the BDCP’s head, intended to hold the project up for far longer than the 50 years it was slated to take in the first place. By which time we’ll all either be

a) dead,

b) in the post-Singularity age of spiritual machines and not in need of water, or

c) drinking desalinated ocean water or water distilled from the vapor out of the air or some other result of currently unimaginable technological advancement that nullifies the need for Delta water altogether.

Which latter hypothetical amounts, odd as it may seem, to the most optimistic argument against doing anything. But can we wait that long? Is it a good idea to bet that technology will outpace the cost of water in a decade, decade.5, which is how long tunnel construction is likely to take? Or will it be more like twenty years, or thirty-five, of doing nothing and hoping, like the good ole WASPs that got us into this mess, that by ignoring something we can negate its potential for harm, that we can deny it right out of existence?

Which kind of is what California in general, aside from just the Delta, is built on. Mike Davis’s book The Ecology of Fear is a great take on how Los Angeles is “a city deliberately put in harm’s way by land developers, builders, and politicians, even as the incalculable toll of inevitable future catastrophe continues to accumulate,” but we can extend that out to the Golden State’s other big cities, too. Especially San Francisco, whose residents were praised across the globe for the speed with which they rebuilt their shaken and burned city in the wake of the 1906 earthquake. Which, like, maybe wasn’t the best thinking in the world, amirite?

This is what I meant last week when I said the water industry deals with fundamental questions of human nature. Our intent is to control our surroundings, to mitigate risk, and we think that we’re able to do that with a fairly high degree of success. But two things belie this.

One: it’s only a gamble, and Mother Nature is the house. Pick any of the pipelines or canals that bring water to millions and millions of people in SoCal and trace it on a topo map for a few miles. It or one of its tributaries will cross a significant seismic fault. Most of this infrastructure is old enough to not be anywhere near “seismically sound,” and there are people whose job it is to determine whether it’s worth spending the money it would take to make these pipes and canals strong enough to withstand a 7 or 8 or 10.3 magnitude earthquake. Besides which, nature’s always got something bigger and better up her sleeve, and we usually only build to withstand the previous worst case scenario. Which is why “unforeseen disasters” keep breaking, right?

Anyway, the answer to whether saving lives is “worth” the money is always, “Yes – if you have it.” But we don’t have it.

And – Two: we probably wouldn’t spend it if we did. We like shiny objects. We like shiny objects and we like lounging around and we like watching football and drinking beer and taking our families out to dinner and buying our girlfriends jewelry and doing things that make life seem pretty nice, or at least okay. Dealing with existential questions on the magnitude of “One” does not fit into that “nice” or “okay” model. We don’t want to be reminded of our fragility, of the fact that our continued existence is at the pleasure – nay, the whim – of Mother Nature. We want her sunshine, we want her good weather and nice beaches and lack of snow and decent fruit. But to lay some cash away to keep ourselves going in those places, against whatever rain she may send our way? Thanks but we’ll spend our money somewhere else.

We’ll spend it to build houses hanging over the edge of a cliff, or at the bottom of an active volcano, or on stilts above the ocean. Think about that, especially you post-Sandy East Coasters. Houses on stilts. Above the ocean.

Sticks versus the Atlantic Ocean.

It seems crazy when you put it like that, but that’s what we do.

And it’s kind of nice to think that we’re all just gamblers. There is so much risk in everything we do that if you look at it, you wouldn’t do it. A friend of mine once asked me, about surfing, “Aren’t you afraid you’ll get eaten by sharks?” I said it’s better odds than getting hit by a car on the freeway, and he said, “Not true. I may die on the freeway, but I can guarantee you the risk of me getting eaten by a shark is absolutely zero.”

“How’s that?”

“I don’t go in the ocean.”

We can pick and choose to control certain odds, but all in all, we’re just rolling craps. For the young and the old and the rich and the poor and the black and the white alike, the inscrutability and awesome indifference of nature levels any playing field you can come up with.

Remembering that we’re on “borrowed time” and that we’re all in this boat together reminds me to take it a little easier, to take myself and my million little plans and strategies a little less seriously.

Not that doing so keeps you from getting thirsty, though.

So, while I may not be doomsday prepping any time soon, keeping a little extra water around the house probably isn’t too bad an idea.

Anyway, now that you’re caught up** on the State Water Project and the current state of water in California – on the various hues and depths of the shadow of the catastrophe we Angelinos live in – let’s hear from you.

What shadows do you live in?

Do you worry about them?

Do you do anything about them?

.

*Kind-of-not-really. Look here for some of the more level-headed opposition.

** I know, I know, this isn’t the whole story. Nor is the SWP the only water issue in California. I’ve ignored a lot of history here that’s actually really really good context for the bitterness felt by both sides of this debate, such as the desiccation of Owens Valley and Mulholland’s Folly. Cadillac Desert is a good place to start if you’re interested in a great narrative of the wildest aspect of the West.

Water wholesalers in eastern Ventura County, and most of the Greater LA Area, including parts of the OC and the Inland Empire, have decent amounts of storage, enough for about 6-9 months depending on usage and weather. But anything serious enough to take out the Delta for that long is going to take a lot longer than that to fix. Beyond that, LA and areas south and east of the city have or can get Colorado River water, meaning they’ll continue to at least be able to drink and eat and feed their pets and wash their children. Eastern Ventura County has no other source. None. There is no physical connection to the system that drains the Colorado River. The City of Ventura and Ojai aren’t going to send over any of their water – they have their own mouths and hippies and horses to keep hydrated and hygienic. And there isn’t much more than a couple months’s worth of even seriously reduced demand in our groundwater basins to support the entire area. And as of now, there aren’t any ocean desalination projects even being conceived around here (except right here, not At but inside the Wellhead, if you know what I mean). And, as an added benefit, all the farming that’s taken place over the years and all the groundwater pumping has led to such serious land subsidence that a lot of the Delta floor is 20, 25, even 30 feet below the tops of the levees, which happen to be right around sea level. Meaning if the ocean somehow backs up far enough past the Carquinez Strait and tips over into that low-lying Delta, it’ll set up a siphon like God’s own firehouse and turn those 1,100 square miles into the Great Salt Lake West.

Water wholesalers in eastern Ventura County, and most of the Greater LA Area, including parts of the OC and the Inland Empire, have decent amounts of storage, enough for about 6-9 months depending on usage and weather. But anything serious enough to take out the Delta for that long is going to take a lot longer than that to fix. Beyond that, LA and areas south and east of the city have or can get Colorado River water, meaning they’ll continue to at least be able to drink and eat and feed their pets and wash their children. Eastern Ventura County has no other source. None. There is no physical connection to the system that drains the Colorado River. The City of Ventura and Ojai aren’t going to send over any of their water – they have their own mouths and hippies and horses to keep hydrated and hygienic. And there isn’t much more than a couple months’s worth of even seriously reduced demand in our groundwater basins to support the entire area. And as of now, there aren’t any ocean desalination projects even being conceived around here (except right here, not At but inside the Wellhead, if you know what I mean). And, as an added benefit, all the farming that’s taken place over the years and all the groundwater pumping has led to such serious land subsidence that a lot of the Delta floor is 20, 25, even 30 feet below the tops of the levees, which happen to be right around sea level. Meaning if the ocean somehow backs up far enough past the Carquinez Strait and tips over into that low-lying Delta, it’ll set up a siphon like God’s own firehouse and turn those 1,100 square miles into the Great Salt Lake West.

(Though at the same time I don’t mean to overstate how “hard” it is – even ultra-marathon-running

(Though at the same time I don’t mean to overstate how “hard” it is – even ultra-marathon-running

Don’t get me wrong – they’re not simpletons or noble savages. They have their shit to deal with, and their interests are wide and their understandings of the world deep and some of them are dedicated to a lot of things outside of work, but to a certain degree, they’re parking in the shade. It’s a pretty cush gig – at least, not a whole lotta what you call whip-cracking. Plenty of people would love to have this job, and most everyone here is to proud to, and most of them are grateful for it, “especially in this economy” and all that. So it seems kind of reductionist of me to say, “Meh, it’s just my day job, whatever, it’s not even a big deal.” That’s where my self-confidence and goals (daydreams) and discontent tip into arrogance. And I find myself there quite often.

Don’t get me wrong – they’re not simpletons or noble savages. They have their shit to deal with, and their interests are wide and their understandings of the world deep and some of them are dedicated to a lot of things outside of work, but to a certain degree, they’re parking in the shade. It’s a pretty cush gig – at least, not a whole lotta what you call whip-cracking. Plenty of people would love to have this job, and most everyone here is to proud to, and most of them are grateful for it, “especially in this economy” and all that. So it seems kind of reductionist of me to say, “Meh, it’s just my day job, whatever, it’s not even a big deal.” That’s where my self-confidence and goals (daydreams) and discontent tip into arrogance. And I find myself there quite often.

I have to imagine this results in part from a very American sense of entitlement. We’re taught that self-employment is the key to happiness, or at least that it’s the full embodiment of the American ideal, and that it’ll bring us riches and a sense of self-sufficiency unrivaled by the drudgery and servitude of working for someone else. One of the more nefariously defeating Myths of America is that everyone can and should make his own way to greatness in the world, when really that’s just simply not possible, for a panoply of reasons we all know by now (right? Right).

I have to imagine this results in part from a very American sense of entitlement. We’re taught that self-employment is the key to happiness, or at least that it’s the full embodiment of the American ideal, and that it’ll bring us riches and a sense of self-sufficiency unrivaled by the drudgery and servitude of working for someone else. One of the more nefariously defeating Myths of America is that everyone can and should make his own way to greatness in the world, when really that’s just simply not possible, for a panoply of reasons we all know by now (right? Right).

B) The actual illusions of psychedelic experience aren’t real illusions, really. They’re metaphors or examples – gateways at best and nightmares at worst. Those feelings of interconnectedness and bliss? They’re just chemical euphoria. I’m with George Harrison, who said that ultimately, it’s a false insight that psychedelic drugs give you, just the tip of the iceberg, and with

B) The actual illusions of psychedelic experience aren’t real illusions, really. They’re metaphors or examples – gateways at best and nightmares at worst. Those feelings of interconnectedness and bliss? They’re just chemical euphoria. I’m with George Harrison, who said that ultimately, it’s a false insight that psychedelic drugs give you, just the tip of the iceberg, and with